Several weeks ago, I noticed a teacher grading some papers. I don’t remember where I was, but I wasn’t at school, and I didn’t know this teacher. As I watched more closely, I saw her writing “-1”, “-3”, “-2” in the margin and then, after finishing with the paper, adding up the deductions and writing a score on the top. At first, I was puzzled by this teacher’s actions, and then I realized that she was grading papers. This realization was quickly followed by the surprise that, just a few of years ago, I graded papers in the exact same manner.

My brain is wired such that I adapt to new situations pretty quickly and often forget things from the past, especially if those things have a negative connotation. So, while you may be skeptical that I actually forgot how to grade papers traditionally, I assure you that my initial confusion was genuine. Fortunately for my students and me, I now provide feedback in a different way and actually [enjoy doing so](https://pedagoguepadawan.net/10/ilikereadinglabreports/). This experience combined with the end of the school year has put me in a reflective mood.

I offer these reflections on how my approach to teaching has changed over the past few years not so much as a model of what should be done but more as a testament that it is possible to implement significant changes and, while these changes may seem daunting at first, in a relatively short period of time, they can become second nature.

Three years ago, everything that happened in my honors physics class was worth points. I checked homework almost every day and recorded points. I kept track of which students presented their solutions to problems to the rest of the class so I could record points. I stamped assignments that were submitted late so that I could calculate a late penalty when recording points. Every lab was collected and points recorded. There were opportunities to get extra points. I would pass back an exam so students could see how many points they lost and then we would begin the next unit. Students focused on collecting as many points as they could. Some played this game exceptionally well.

Two years ago, my colleague and I realized that these damn points were distracting our students from focusing on learning. We [wanted certain things for our students](https://pedagoguepadawan.net/37/whysbg/) and standards-based grading seemed like it could help.

It has. Two years ago we adapted a colleague’s implementation of SBG to our honors physics class. This past year, we [made some changes and adapted our approach](https://pedagoguepadawan.net/22/threerealizations/) to our regular physics class team-wide. Last semester, we made some [more tweaks](https://pedagoguepadawan.net/31/adjustmentsforsecondsemester/) to the implementation in regular physics. Now the [entire school is moving towards some form of SBG](https://pedagoguepadawan.net/23/growingsbarschoolwide/).

Two years ago when we embarked down this path, I had many concerns about the implementation of SBG. What helped me to put these in perspective was comparing this new approach with what would have been done in previous years. I asked myself, “Yes, it may not be ideal, but is it a step the right direction?” Some of my concerns were:

* Students won’t do labs if they aren’t graded. *If the labs are engaging (not cookbook) and you have established a classroom culture that values learning, they will. If they don’t, maybe you need to revise that lab.*

* Students won’t study for exams if they have multiple opportunities. *Some won’t. Some didn’t before. They get to prioritize and make choices. Learning to do that and the consequences of their choices in a valuable skill which is better practiced in high school than college.*

* Students will get behind and can’t catch up. *Some do and can’t. Some do and can. At least now they have the opportunity to catch up instead of being left behind as the class plows onward. Before SBG, I can remember only one student who would go back and study topics they still didn’t understand after the exam. Now almost every student does.*

* I will be overwhelmed creating multiple assessments. *It was work but not overwhelming since we split it. We limited reassessment opportunities and leveraged technology where feasible.*

* I will be overwhelmed with students assessing multiple times. *When a line formed out the door of my classroom the afternoon after our first exam, I realized I would have to set some boundaries. Reassessments are offered one day a week before and after school. Period.*

* I will be overwhelmed grading reassessments. *Grading reassessments is more grading, but checking for understanding is faster than deducting points. Overall, I do a lot less grading and provide a lot more useful feedback.*

* Parents will revolt. *Many were extremely supportive. Some couldn’t let go of the points game that their child had learned to play so well. Some couldn’t focus on anything other than the GPA that will be on a transcript for college. Patience, open house discussions, and phone calls help.*

* Students will revolt. *If you take the time to share the rationale for the structure of the class, discuss their concerns, and truly change your philosophy of education, [a strong majority of students prefer SBG](https://pedagoguepadawan.net/33/studentfeedbackonsbar/). After a career of playing the points game, some students are so frustrated that the rules of the game have changed, that they can’t adjust. I don’t give up on these students, but I’m not always successful in changing their perspective towards learning.*

The past two years haven’t been easy, and there have been some [challenges which could have been avoided](https://pedagoguepadawan.net/26/unfriendlygradebooks/). However, these past two years have been extremely rewarding. I feel that I spend my limited time in ways that benefit student learning. I feel that many students are once again focused on learning and understanding.

The best indication that I’m on the right track is that I can’t imagine teaching like I did two years ago.

As one of the last students of non-SBG physics taught at North, I felt that the points system provided a reasonable mechanism of feedback for students who were able to translate low scores into plans of action to develop a stronger knowledge of future subjects. The problem was that there weren’t many of them.

The points system didn’t provide a mechanism of learning. It provided a way to make educated decisions on what to do and what not to do. Any AP student can attest that receiving top grades in six college-level classes while maintaining strong extracurricular involvement in order to gain college acceptance means learning only as much as necessary to receive those grades. Each week, I would review my course grades and would set priorities on which assignments would and would not be completed. That usually meant never doing physics homework, not checking lab assignments, and handing in rough drafts as final copies.

This procedure resulted in fragmented knowledge that never should have yielded college credit (yet did), but allowed respectable GPA’s during the few semesters when implemented. It encouraged spreading my capabilities as thin as humanly possible. And, when I entered college, I realized that I did not know how to learn effectively enough to receive the sort of grades I had in high school.

At one point during my first semester in college, I decided to stop worrying about immediate feedback on assignments and instead focused on long-term course objectives. I addressed those in the ways that I thought were necessary, and used homework more as a test of my knowledge instead of a means of learning. This standards-based learning philosophy pushed my exam grades up , moving from one to two or three standard deviations above the class average, but also took up easily twice as much time. I had to drop almost my entire extracurricular involvement to ensure that I was addressing each of my home-made objectives properly. Still, my grades rose above those I earned in high school.

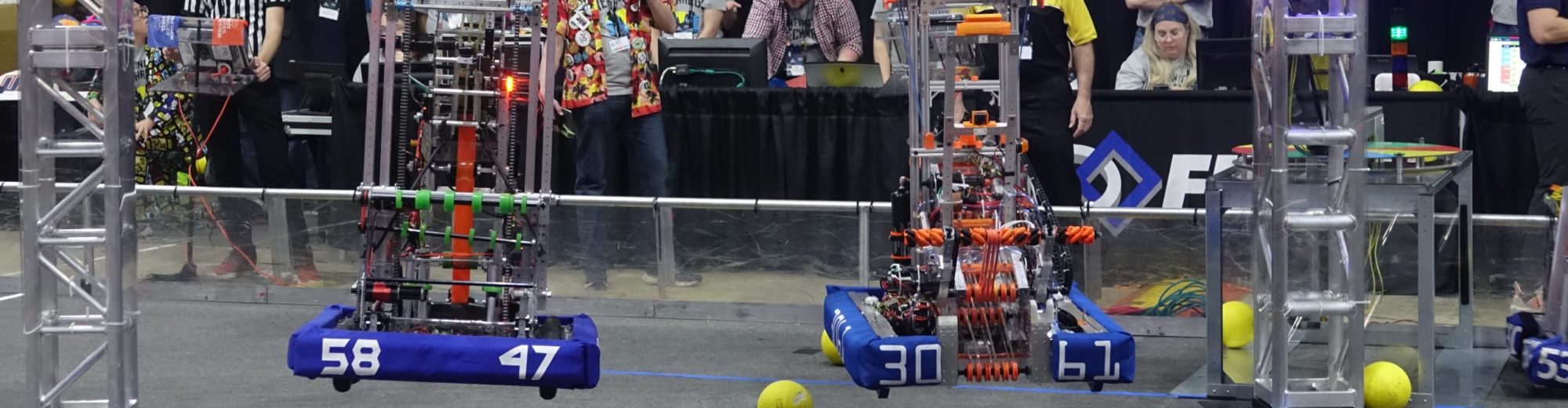

In my view, points-based systems facilitate thin, fragmented learning that can be treated as an optimization problem to allow students to take on more challenges at one time, while a standards-based system facilitates cogent, in-depth knowledge that cannot be optimized to look good without deep understanding. Now, even though it may provide stronger understanding, I certainly can say that if I had to demonstrate actual mastery of Physics C concepts instead of just “A- level” proficiency, I may not have had time to be involved in the FIRST team. It’s without a doubt a trade off.